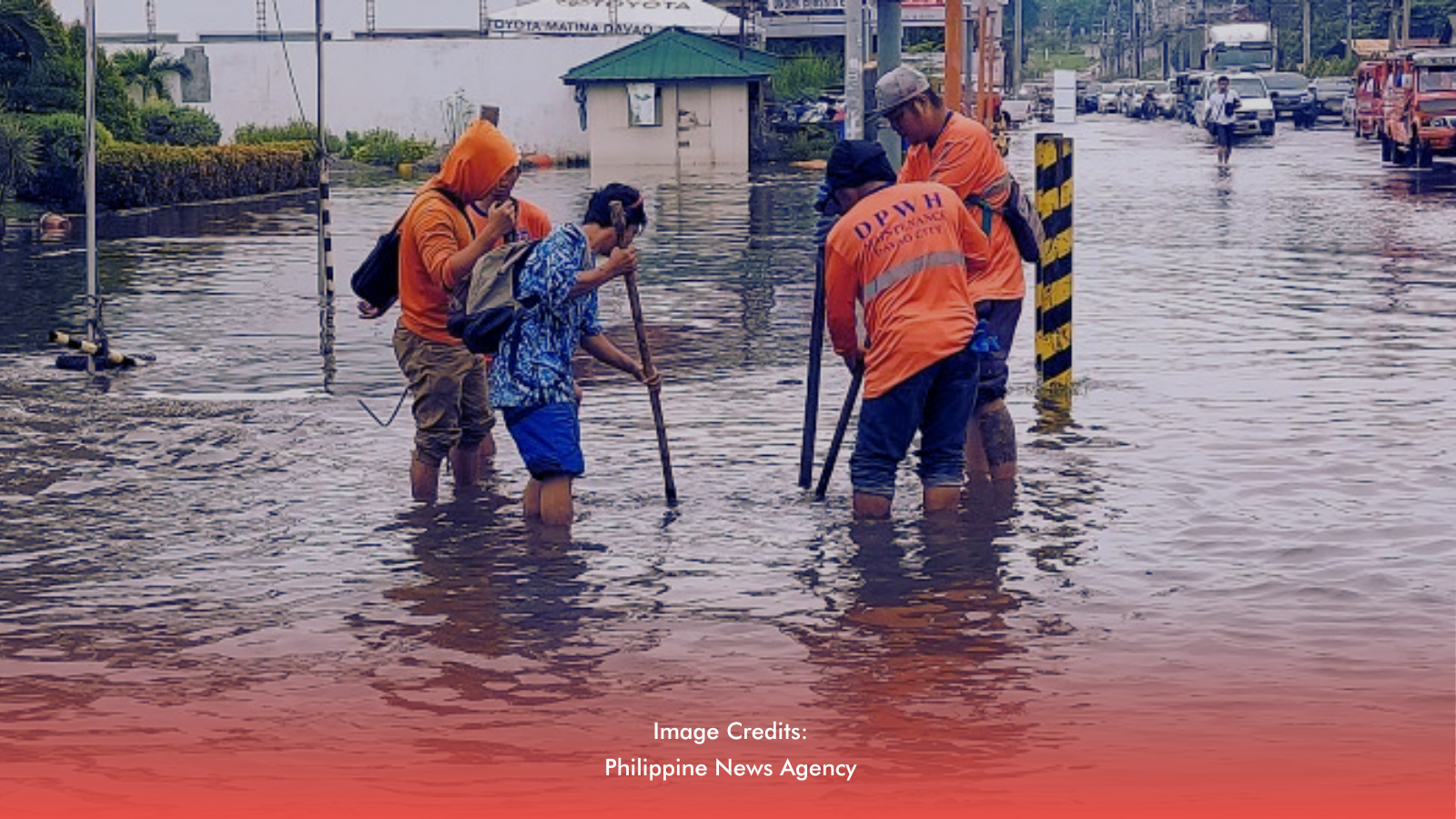

For decades, flood control in the Philippines has been managed largely by national agencies such as the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH). Yet, despite billions in funding, flooding remains a recurring crisis in many cities. The idea of shifting this responsibility to local government units (LGUs) raises the question: would localized management lead to better results?

Former Manila Mayor Isko Moreno Domagoso has suggested that giving mayors operational control over flood control facilities could improve accountability and speed up problem-solving. In this model, the officials who directly face constituents during floods would also be the ones responsible for prevention and mitigation. The expectation is that local leaders, aware of the political cost of failure, would prioritize efficiency over bureaucracy.

RELATED: [#BahaPH: Land Subsidence, Metro Manila’s Silent Enemy]

From Centralized Oversight to Local Control

Under the current system, DPWH holds the largest share of the flood control budget — P34 billion for Metro Manila alone. However, many projects have been criticized for delays, incomplete construction, or poor functionality. In contrast, the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA), with a much smaller P2 billion budget, operates 72 pumping stations across the region, including 24 in Manila, and has been noted for keeping most of them functional.

If LGUs were given authority similar to the MMDA’s operational role, flood control projects could be more aligned with the specific needs of each city or municipality. Local governments could schedule maintenance based on weather patterns, address equipment breakdowns immediately, and ensure that facilities are operational before public launch.

Potential Benefits and Risks

The potential upside is a system where residents can hold local officials directly accountable. Instead of multiple layers of national oversight, decision-making could be faster, procurement could be more localized, and coordination during storms could be more seamless. Mayors, knowing their performance is under direct public scrutiny, might also push for innovative approaches, from better pumping technology to community-based flood monitoring.

However, decentralization comes with challenges. Not all LGUs have the same technical capacity or financial discipline. Without strong safeguards, the shift could risk uneven service quality, with wealthier cities benefiting more than less-resourced ones. Clear national standards and periodic audits would still be necessary to ensure equity and prevent misuse of funds.

In the end, the proposal reframes flood control as not just an engineering challenge but a governance issue. Whether the responsibility stays with national agencies or moves to LGUs, the key question remains: who is best positioned to deliver lasting protection for communities facing the next big storm?

RELATED: [‘Shame On You’: Marcos Blasts Corruption In Flood Control Projects]